No walks for us today. We are being picked up at 9am to go to our cooking school with Dewa, who will take us to his village and his ancestral home to teach us traditional Balinese recipes. Right up our alley!

Dewa is there for us, right on time (we have him – and everyone – pick us up at ShananaMama, the restaurant on the corner of our little soi – our street is just too narrow and torn up with construction to ask people to drive down to pick us up, when we can easily walk). We hop in his car, and away we go. At a snail’s pace, because of course, traffic is dense at this time of day. But we don’t care, we are on our way out into the countryside to Keliki, the village Dewa has lived in all his life – and his parents and their parents, etc., etc., before him.

Along the way, Dewa talks about the village, his family has lived in the same house for 1000 years. He talks about how the entire village is self-sufficient. They grow what they need to eat and survive, and sell any excess, using the profits to fund different things in the village, like repairs, items for the community temple, etc. During the pandemic, they gave away the excess food they grew to others who needed it. Everything is about being a good person, being good to yourself and others. Plus, they live for today – they believe that today is the last day. You should grow what you need to eat only for today. You should live your life only for today. Tomorrow may not come, so live and do good for today. Then if tomorrow does come, do it all over again. Great philosophy.

As an example of this philosophy played out in real life, before their current President, who has done many good things for Indonesia, the government was much more corrupt. Government employees, particularly the police, were very corrupt and looked for bribes everywhere. The police would stop you for no reason, and the people would give them 10,000 IDR for a bribe. Not more, just 10,000. Because they understood that the police were not paid a good living wage and could not afford to live on their salary. So the Balinese people believed it was a good and charitable thing to give the policeman 10,000 to help them in their life. Same with teachers! Each child needs a school uniform which costs 50,000 IDR. Teachers would charge 60,000 IDR because they also were not paid well and needed extra money to survive. And again, the people did not mind because this was being good to the teachers. They called this “polite” bribery!

The villagers also don’t believe in birthdays. Since every day is last day of life, there is no need to know anyone’s birthday or their age. To determine if children are old enough to go to school (typically at 6 years of age), they must have/be able to do one of the following: have 2 adult teeth or be able to reach one hand over their head and touch the other ear or trill their r’s. Thank heavens you don’t need all 3 – I’d never be able to go to school as I can’t trill my r’s for love nor money (reference my speech therapy in 1st and 2nd grade because I had a NY accent and couldn’t pronounce r’s).

Dewa also explained that all the houses are the same. They are laid out in identical style, no one has a front door. But everyone has 3 dogs – for doorbells! And 2 cows for plowing the fields, and 2 chickens for sacrifice and more ducks than they can count to eat the insects and weeds in the rice. They also grow rice here differently. It isn’t in the field under water, it is grown in a garden. The texture is different too. It is more like grass with a hard texture and less sugar.

WE learned a lot on our 30 minute drive from Ubud to his village in Keliki (which he called something else that I could never quite get – it was sort of like Mon Duc Taro – but that isn’t anywhere on the map and it would be no surprise if I completely misheard him!). At any rate, we finally arrive in the village and go for a walk in the forest to his family’s garden. Along the really muddy (it has been raining every day the past week) path, we stop to look at different trees and herbs and spices that are growing. Many of which are not even used in Balinese cooking – like clove and vanilla and chocolate. There is an abundance of it here, and it is simply not used in traditional cooking.

Reaching Dewa’s garden, we wash off our feet (good call Ed on wearing our flip flops!) and commence to follow him around the garden while he tells us about all the plants, quizzes us on what he is selecting and watching him put together a bundle of really fresh produce for us to use in our cooking. Talk about farm to table!

Leaving the garden, we walk through more jungle like areas – this time mercifully on pavement – to the top of the village rice fields which are so incredible pretty and full of rice ready to harvest. Continuing on, we head into the village proper, passing buildings now (some of which Dewa says are foreign investors building 2 stories when there are earthquakes here – he is not positive on this development, and to his point – one of the 2 story houses has a huge crack between the 1st and 2nd story), before arriving at his lovely traditional house where his wife, Jero, and daughter Natalie await us.

Here we sit on the edge of one of the open air ceremonial rooms to chat with Dewa about the house. He points out the bedroom where his parents and he, his wife and his daughter sleep (parents in the bed, everyone else on the floor). He walks us through their temple and points to the ceremonial sleeping room where he and his wife go at certain times of the month for sleeping together. He shows us the 2 kitchens – one for the women to use on a daily basis, the other (the one we will be using) for the community where the men will cook for bigger eating events. And then he points out where the placentas are buried after a child is born. There are two places – one on each side of the ceremonial sleeping room – where female placentas (on the left) and male placentas (on the right) are buried. The placenta burial also determines the name of the child. The villagers suggest names written on paper with incense burning around the paper. The name that does not burn – or is burnt the least at the end of the ceremony is the name. His daughter was actually named by some Canadian guests who were taking a class during the ceremony. They asked if they could suggest a name, and their name was the one the placenta “chose.” So Natalie is the first person in the entire village to have a Western name.

All of this is so totally fascinating! We could sit here and listen to Dewa for hours. And, even though we know this is his job and career, it all seems so personal that we don’t even feel comfortable taking pictures around the house. I’m sure we could have, but it just didn’t feel right. So we have 1 picture of the bedroom. At least it will give you some idea of the house and the style and architecture.

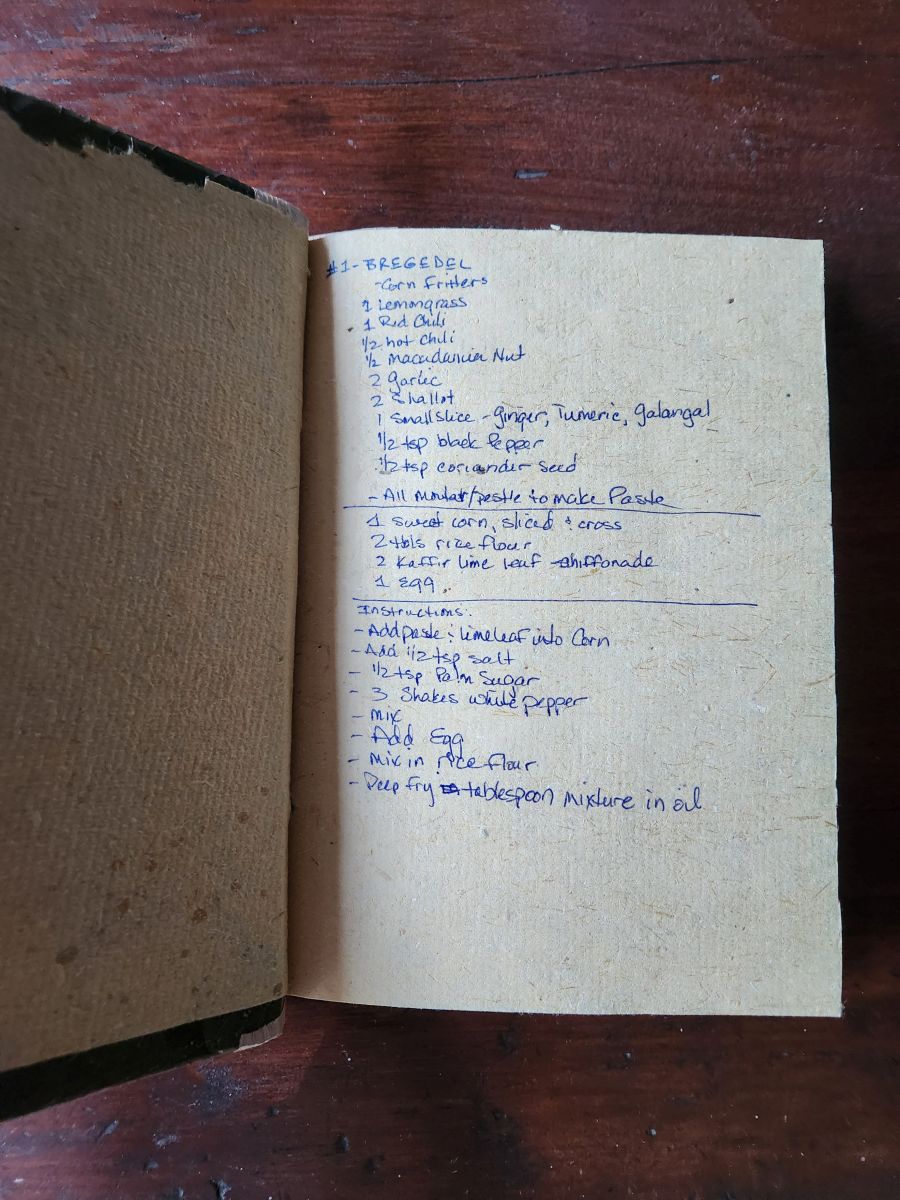

Now it is time to cook! We move over to the communal kitchen where Jero is there to help and most of the prep work has been done. We will be making 6 different dishes today, and one of the greatest things is that Dewa gives us this locally produced notebook made of parchment with a shellacked or lacquered leaf cover in which to write all the recipes. That’s so great! So, while I dutifully copy what Dewa says, Ed dutifully prepares the ingredients as Dewa calls them out. And Jero makes a paste with all the vegetables Ed is dicing and slicing. This is too fun!

Everything we do is traditional. From the lemongrass tea we are drinking, made from boiling a knotted piece of lemongrass (which is most delicious I might add – and this from a tea-hater) to the way we make the coconut milk – by kneading shredded coconut together with spring water until the water turns white. Too cool. While most of the cooking is done by Jero, over an open fire wood stove no less, I do get to get my hands dirty a bit by stir frying up the Bekuah, the chicken in coconut sauce.

Then it is time to feast! We have prepared, so to speak, Bregedel (corn fritters), the aforementioned Bekuah, Tum Ayam (chicken wrapped in banana leaves then steamed), Tempeh Manis (fermented soybean in palm sugar and stir fried), Urab (the fabulous vegetable salad with coconut shreds) and for dessert Godoh (fried bananas).

Oh, and what a feast it is! Everything is absolutely delicious. And far too much for us to eat all in one sitting. So Dewa and Jero make up little banana leaf packages with our leftovers for us to take home for dinner tomorrow night. What an excellent experience!

While we’ve been eating, Dewa has walked back to pick up the car we left at the other side of the village, and we commence our drive back into Ubud proper and to the top of our little soi.

Groceries stowed, we hang out a bit then decide we want an afternoon beverage, traipsing down to a restaurant on the corner of Jaya and Bisma that isn’t open yet, but stumbling on Milos Garden, a lovely oasis up a big flight of stairs above the place we were trying to visit. This is a find. It is a lovely garden (see the name) with statues and greens and fantastic seating areas, a full bar – and no one there but us. The menu looks great as well, so we are definitely adding this to our list of places for dinner.

Later we strike out again, this time heading down our street toward the Monkey Forest to walk up Monkey Forest road and explore the different bars and restaurants there. Except for the random monkey sightings…

…it isn’t all that interesting – way more crowded and much less comfortable than our little area one street over. We do stop for a drink at a place called Donna, which is really super expensive and definitely not our kind of joint, but they were open, they had wine, and it was a lovely place to sit and enjoy a beverage – and watch the stupid girls who we just KNOW thought they were “influencers” take pictures of their strategically placed big old name brand (probably knock off) purse. Sigh. The scourge of social media.

And then it is once again, in for the night. We are still stuffed from lunch and there is no need to go out and make it worse by stuffing our faces!