It’s not the prettiest day today, overcast and chilly, but we’re dressed for it – and truly, we’d rather be chilly than hot and sweaty. After a lovely breakfast – anything and everything you’d want – we split into two groups – one (including Raul and Lori) who are going up to Veliko Turnovo, where we toured a few days ago, the other (us) taking a walking tour of Ruse. We meet our guide at the foot of the gangway at precisely 9:30a and off we go.

Along our 15 minute walk into the center of town, we learn that Ruse means blonde (but actually I think this is a bit of a translation error, because other reference materials say Ruse is derived from the word rusa, meaning brown hair) and legend has it that the city got its name because they worshiped a blond (or brown hair – take your pick!) goddess in medieval times. Ruse is perched on the highest shore of the Danube and was once considered one city with Giurgiu, across the banks of Danube. Now, of course, they are separated, with Ruse being the 4th largest city in Bulgaria with a centralized city center and a 4km walking zone that makes it easily reached from just about any point of the compass.

After a nice little walk, we arrive at Liberty square, considered the “new” square as it was built in 1880, supposedly on a former Turkish cemetery. We tour around the virtually empty square, which is a actually a lovely garden area, with the Statue of Liberty as its centerpiece. The statue was sculpted in 1908 with Liberty pointing north, toward Russia, because they came and defeated the Turks. The statue represents Bulgaria, ready to “protect herself and to be free,” according to our tour guide.

Moving to the outskirts of the square, we begin to tour past incredibly beautiful ornate Rococo and belle-epoque style buildings. You can easily see how Ruse was (and still is, we suppose) Bulgaria’s wealthiest city, and equally understandable why the city is called “little Vienna” for its architecture.

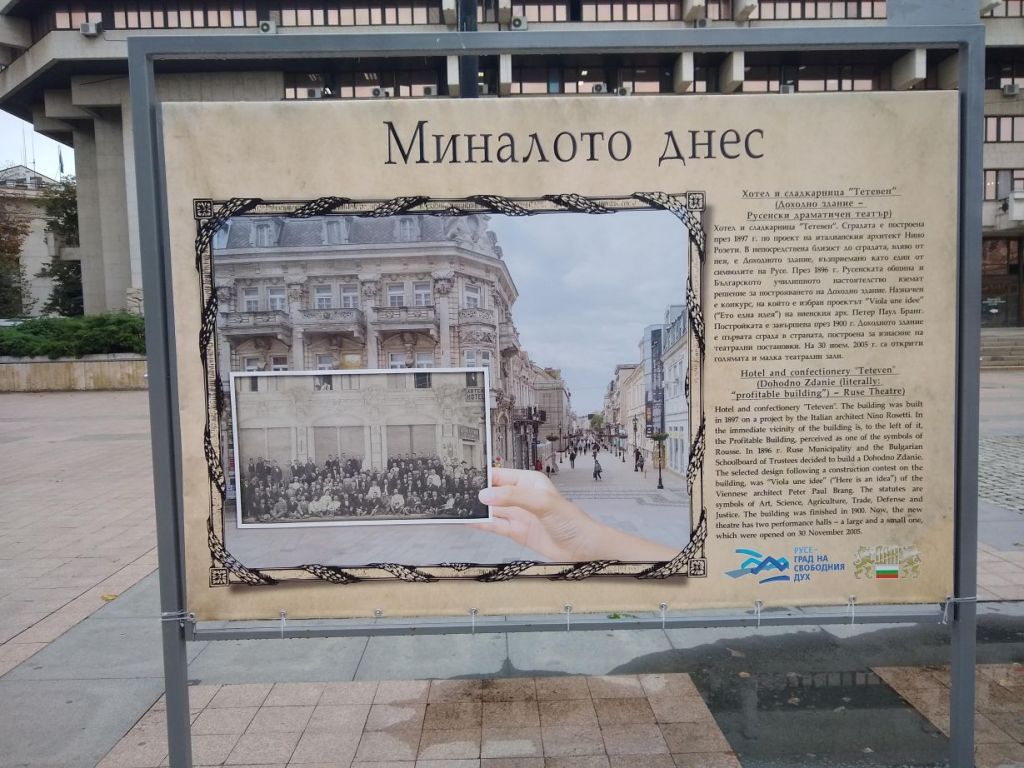

Wandering around the square, our guide explains that originally buildings were required to be grey so that no one would dream, everything would be the same every day. Now there are splashes of color, such as the Opera House painted a vibrant red. Heading back into the center of the square, we pass by the Pyce letter statue, Pyce being the Bulgarian word for Ruse, then explore some odd 3D paintings displayed around the main fountain. We try to capture the 3D spirit, but for some reason we aren’t as successful as we when we last visited the Chiang Mai “tricky-eye” museum. We also have time to look at some great touristic displays around the square that depict an existing building juxtaposed against an old photo from the 1800 or early 1900s. Really fun and fascinating way to explain the historical significance fo the area.

Our next and final stop on our walking tour is the Holy Trinity’s Church (or the Church of Sveta Troitsa). A Bulgarian orthodox church built sometime in the 17th or 18th C (not sure exactly which), but it is the oldest church in the city. An imposing structure made of heavy looking stone and embellished with Baroque (I think) pillars and arches, an interesting feature is that the nave is 13 feet below street level, due to Ottoman empire requirements at the time that churches could not be taller or more magnificent than Mosques.

Inside, the decor is as ornate as ornate can be. Gold, soaring ceilings painted with frescoes, brick arches leading to Roman catacombs, a balcony where choir sings, chandeliers donated by the Russian king after liberation. Some features, such as the stained glass is new and pictures dragons fighting against the cross which is a symbol of the eternal fight of good and evil. Incredibly spectacular, especially since even though Ruse was the wealthiest city, wealth is still relative – especially today.

Another interesting fact is that churches were not closed down during communist times. The ruling government didn’t want people worshiping, but they had nothing against tourists paying entrance fees! The communist government had a divide and conquer strategy, thus they didn’t want people gathering together at church to eliminate the possibility of insurgence. In addition, they recruited priests as spies. Priests who refused were sent to concentration camps. During those times, 80% of all priests were cooperating as secret police. Even the Patriarch was elected by the communist party, even though the people thought he was elected by church.

The government was big on “tricks” to keep people from going to church. During big holidays like Easter and Christmas, the communists started airing Western movies on TV so people would stay home to watch instead of going to church. At Easter, Bulgarians make a special bread called Kozunak, which literally takes all day to make and bake. The communists repeatedly told the people Easter was nothing important, and to prove it, they started making Kozunak through industrial bakers and selling the bread very day. Then they said, “See, it’s nothing special, you can eat Kozunak every day.” In these ways, Bulgarian leaders differed from their Romanian counterpart, Ceausescu. Not only were they much more sly, they also hid their wealth from the people and didn’t flaunt it like Ceausescu.

Exiting the church, our guide walks us back to the main square where she sends us off on our own adventures for the rest of the day. For us, this means the a nice walk back to the ship, a quick lunch and then we are off to the Transport Museum for our afternoon touring.